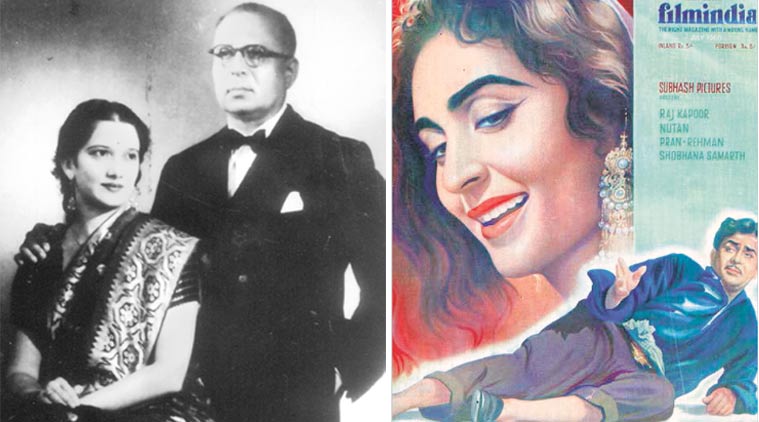

12th NOV 2015 DR. BABURAO/SUSHILA RANI PATEL OF FILMINDIA MAGAZINE 1935 trishagupta.blogspot.com

Dr. BABURAO PANDURANG PATEL BIRTH:- 4th APRIL 1904 - 1982

Book Review: A legendary ‘character’ from Hindi cinema’s early days

A book review, published in the Sunday Guardian:

Sidharth Bhatia’s book on Filmindia magazine and its founder Baburao Patel reminds us of a colourful man who embodied many of the conflicts of his time.

Over the period 1948-54, sitting in Lahore, Saadat Hasan Manto produced a series of sparkling pen-portraits of people he knew well in the Bombay film world of the 1940s. Some of those featured in Stars from Another Sky (1998) are still famous in our time, names like Ashok Kumar or Nargis, while present-day movie buffs might be hard-pressed to recognise others: comedian V.H. Desai, “Too Hot to Handle” Kuldip Kaur, or “Pari Chehra” Naseem, who was also Saira Banu’s mother. But they were all actors — except one: Baburao Patel.

That Manto chose to include him speaks of Patel’s importance to early Bombay moviedom, and his reputation as a “character”. Sidharth Bhatia’s new book re-certifies his legendary status. His Filmindia, founded in 1935, quickly became the most influential magazine on Hindi cinema, characterised by its editor’s brash opinions, rough-and-ready humour and appetite for industry gossip. It held on to that position for nearly two decades, before dissolving — like Baburao himself — into a strange brew of right-wing Hindu politics and crude sexual frisson.

Baburao’s journalistic career began with the trilingual (Urdu, Hindi, English) Cinema Samachar, and Manto himself mentions two other publications he started during the Filmindia years: Prabhat “which would publicise, but in an original way” the films produced by Prabhat Film Company, and an Urdu weekly called Karwan, which Baburao started to help a friend called Abid Gulrez, and then revived for Manto.

Baburao was also the rare film critic to have been a director first — rather than the other way round, as seems to be the norm. Of his six films, four were made before he launched Filmindia — Sati Mahananda (1933), Maharani (1934), Bala Joban (1934) and Pardesi Saiyan (1935). In the 1940s, he returned to direction to make Draupadi (1944) and Gwalan (1946), both vehicles for the acting and singing talents of his third wife, Sushila Rani.

Despite his towering presence, little of note seems to have been published about him in English beyond the occasional mention. Film histories of the time make mention of Patel’s scathing pen, the power his reviews wielded, and his tumultous association with everyone from Dilip Kumar to K.A. Abbas. Meanwhile, the Tamil writer Ashokamitran has reminisced about how his work at Gemini Studios’ publicity department in the 1950s included summarising Patel’s ramblings: “If Baburao Patel had only known how I rewrote the majority of his editorials...”

Sidharth Bhatia’s The Patels of Filmindia is, therefore, extremely welcome. And by weaving the book around Patel’s long-time partnership with Rani, it offers a useful counterpoint to Manto. Manto casts Rani as one of many women in Patel’s life: attractive but insubstantial. (Sample sentence: “Did he think politics was a Rita, a Sushila or a Padma whom he could put on top of a maypole and have it perform tricks according to his instructions?”) In contrast, Bhatia presents Patel through Rani’s eyes — as an impressive man with an indomitable will, but also impossibly demanding, inconsiderate and not as transparent in his personal life as in his public persona: during their courtship, for instance, he got rid of a rival suitor by writing him a letter on Rani’s behalf.

Bhatia’s book is the result of his meetings with the late Rani, and his admiration for her is apparent. We hear about her feistiness, her earning a law degree in her sixties, her impeccable classical training, her 2002 Sangeet Natak Akademi Award and her consistency at riyaaz even in old age. Rani, on her part, seems to have taken the book as an opportunity to speak frankly about Patel, and the eventful life she led with him: from being deputed to teach English to the youthful Madhubala, to campaigning in Raipur in 1971 against the combined might of Congressmen S.C. and V.C. Shukla.

The book paints a revealing portrait of an Indian marriage of a certain era, in which the wife, despite being no pushover, struggles for control over her life, while the husband can’t decide between promoting her talent and throttling it. “Baburao got me teachers but when it came to concerts, he put his foot down. It used to leave me in tears,” Rani told Bhatia. After marrying Rani, he tried to make things up to his earlier wife Shireen by bringing her to live with them in Girnar bungalow in Bandra. He even “started publishing articles on cookery, including a food column, “A La Girnar” in the magazine under her name”. Both women were thus trapped in an unpleasant situation not of their making, while Patel carried on “writing books, thundering in his columns and unsurprisingly, chasing women.”

Patel’s “thundering” shifted in focus over time. From bad films, he graduated to ranting against what he saw as bad policies. By 1957, he was raging against a Censor Board directive against films that “glorify or sanctify social usages, customary practices or other actions which according to modern standards of social behaviour in India are considered sinful or criminal”. He saw this, like much else, as deliberately anti-Hindu action on the part of the Congress. In a 1957 sentence that speaks of his ideological turn, Patel wrote: “Congressmen have come to realise that orthodox and traditional Hinduism is the only force that challenges the secular supremacy of Congress rule in India.”

In 1960, he re-jigged the magazine as a general publication, calling it Mother India. He was not the man to toe a party line, but his views had become largely pro-Hindutva: he even hired as a columnist P.N. Oak, author of various Hindu conspiracy theories, such as the one about the Taj Mahal actually being a Shiv temple called Tejo Mahalaya.

Patel became an MP in 1967. He remained active as editor until the Emergency, when he was thrown into Arthur Road Jail, apparently for some question about Sanjay Gandhi which he had answered with his usual sharp tongue. Although Rani’s letter to Indira Gandhi got him out soon, she told Bhatia that a broken Patel left the magazine to her after that.

Bhatia provides a readable, informative account of a colourful man. The volume is also meant as a sort of archive. This works exceptionally well with images: every alternate page is a glossy reproduction of one of Filmindia’s memorable hand-painted covers, which doubled up as film publicity. It doesn’t work so well with the Filmindia reviews, articles and Q&As which take up the volume’s second half. For one, Patel was no stylist, as is apparent from such headlines as “Purab Aur Pacchim (sic): A Howling Nonsense” and “Zid Gives Incurable Headache: A Picture Rotten All-Round”. His replies to readers’ queries can be glibly funny: “Gandhism these days is a prayer for the poor and profits for the rich”, but are often deeply sexist: “Q: Who can be the best companion for travelling purposes? A: A young woman who eats less, sleeps less and talks less.” Even if we grant that there is value to reproducing this material, it seems a pity that the pieces are not dated, annotated, or illuminated by any critical analysis. Still, Bhatia’s labour of love will certainly revive interest in a long-forgotten maverick whose life and work deserve closer critical study.

Published in the Sunday Guardian, 17 Oct, 2015.

Sidharth Bhatia’s book on Filmindia magazine and its founder Baburao Patel reminds us of a colourful man who embodied many of the conflicts of his time.

|

| Baburao Patel with his wife and editorial assistant, Sushila Rani Patel. |

That Manto chose to include him speaks of Patel’s importance to early Bombay moviedom, and his reputation as a “character”. Sidharth Bhatia’s new book re-certifies his legendary status. His Filmindia, founded in 1935, quickly became the most influential magazine on Hindi cinema, characterised by its editor’s brash opinions, rough-and-ready humour and appetite for industry gossip. It held on to that position for nearly two decades, before dissolving — like Baburao himself — into a strange brew of right-wing Hindu politics and crude sexual frisson.

Baburao’s journalistic career began with the trilingual (Urdu, Hindi, English) Cinema Samachar, and Manto himself mentions two other publications he started during the Filmindia years: Prabhat “which would publicise, but in an original way” the films produced by Prabhat Film Company, and an Urdu weekly called Karwan, which Baburao started to help a friend called Abid Gulrez, and then revived for Manto.

Baburao was also the rare film critic to have been a director first — rather than the other way round, as seems to be the norm. Of his six films, four were made before he launched Filmindia — Sati Mahananda (1933), Maharani (1934), Bala Joban (1934) and Pardesi Saiyan (1935). In the 1940s, he returned to direction to make Draupadi (1944) and Gwalan (1946), both vehicles for the acting and singing talents of his third wife, Sushila Rani.

Despite his towering presence, little of note seems to have been published about him in English beyond the occasional mention. Film histories of the time make mention of Patel’s scathing pen, the power his reviews wielded, and his tumultous association with everyone from Dilip Kumar to K.A. Abbas. Meanwhile, the Tamil writer Ashokamitran has reminisced about how his work at Gemini Studios’ publicity department in the 1950s included summarising Patel’s ramblings: “If Baburao Patel had only known how I rewrote the majority of his editorials...”

Sidharth Bhatia’s The Patels of Filmindia is, therefore, extremely welcome. And by weaving the book around Patel’s long-time partnership with Rani, it offers a useful counterpoint to Manto. Manto casts Rani as one of many women in Patel’s life: attractive but insubstantial. (Sample sentence: “Did he think politics was a Rita, a Sushila or a Padma whom he could put on top of a maypole and have it perform tricks according to his instructions?”) In contrast, Bhatia presents Patel through Rani’s eyes — as an impressive man with an indomitable will, but also impossibly demanding, inconsiderate and not as transparent in his personal life as in his public persona: during their courtship, for instance, he got rid of a rival suitor by writing him a letter on Rani’s behalf.

Bhatia’s book is the result of his meetings with the late Rani, and his admiration for her is apparent. We hear about her feistiness, her earning a law degree in her sixties, her impeccable classical training, her 2002 Sangeet Natak Akademi Award and her consistency at riyaaz even in old age. Rani, on her part, seems to have taken the book as an opportunity to speak frankly about Patel, and the eventful life she led with him: from being deputed to teach English to the youthful Madhubala, to campaigning in Raipur in 1971 against the combined might of Congressmen S.C. and V.C. Shukla.

The book paints a revealing portrait of an Indian marriage of a certain era, in which the wife, despite being no pushover, struggles for control over her life, while the husband can’t decide between promoting her talent and throttling it. “Baburao got me teachers but when it came to concerts, he put his foot down. It used to leave me in tears,” Rani told Bhatia. After marrying Rani, he tried to make things up to his earlier wife Shireen by bringing her to live with them in Girnar bungalow in Bandra. He even “started publishing articles on cookery, including a food column, “A La Girnar” in the magazine under her name”. Both women were thus trapped in an unpleasant situation not of their making, while Patel carried on “writing books, thundering in his columns and unsurprisingly, chasing women.”

Patel’s “thundering” shifted in focus over time. From bad films, he graduated to ranting against what he saw as bad policies. By 1957, he was raging against a Censor Board directive against films that “glorify or sanctify social usages, customary practices or other actions which according to modern standards of social behaviour in India are considered sinful or criminal”. He saw this, like much else, as deliberately anti-Hindu action on the part of the Congress. In a 1957 sentence that speaks of his ideological turn, Patel wrote: “Congressmen have come to realise that orthodox and traditional Hinduism is the only force that challenges the secular supremacy of Congress rule in India.”

In 1960, he re-jigged the magazine as a general publication, calling it Mother India. He was not the man to toe a party line, but his views had become largely pro-Hindutva: he even hired as a columnist P.N. Oak, author of various Hindu conspiracy theories, such as the one about the Taj Mahal actually being a Shiv temple called Tejo Mahalaya.

Patel became an MP in 1967. He remained active as editor until the Emergency, when he was thrown into Arthur Road Jail, apparently for some question about Sanjay Gandhi which he had answered with his usual sharp tongue. Although Rani’s letter to Indira Gandhi got him out soon, she told Bhatia that a broken Patel left the magazine to her after that.

Bhatia provides a readable, informative account of a colourful man. The volume is also meant as a sort of archive. This works exceptionally well with images: every alternate page is a glossy reproduction of one of Filmindia’s memorable hand-painted covers, which doubled up as film publicity. It doesn’t work so well with the Filmindia reviews, articles and Q&As which take up the volume’s second half. For one, Patel was no stylist, as is apparent from such headlines as “Purab Aur Pacchim (sic): A Howling Nonsense” and “Zid Gives Incurable Headache: A Picture Rotten All-Round”. His replies to readers’ queries can be glibly funny: “Gandhism these days is a prayer for the poor and profits for the rich”, but are often deeply sexist: “Q: Who can be the best companion for travelling purposes? A: A young woman who eats less, sleeps less and talks less.” Even if we grant that there is value to reproducing this material, it seems a pity that the pieces are not dated, annotated, or illuminated by any critical analysis. Still, Bhatia’s labour of love will certainly revive interest in a long-forgotten maverick whose life and work deserve closer critical study.

Published in the Sunday Guardian, 17 Oct, 2015.

- See more at: http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/books/the-patels-of-pali-hill/#sthash.aQflsovM.dpuf

Search Results

Lagat Nazar Tori Chhalaiya- Mukesh, Sushilarani Patel ...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgcrVFUZLXE

Jan 24, 2011 - Uploaded by Shrikant Talageri

A beautiful old Hindi film duet of Mukesh and Sushilarani Patel. Sushilarani Patel is the wife of the late Baburao ...Dr. Babu Rao: A short history of SUB-PLAN agitation in ...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTubA1hTLJ4

Feb 11, 2014 - Uploaded by Dalitcamera Ambedkar

Dr. Babu Rao, teaches in Osmania Medical college and also the Officer on Special Duty exclusively for the ...C) Message from Dr Baburao Gurav - YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwTWUh594_g

Feb 11, 2010 - Uploaded by islamvisionpune

पैगंबर मुहम्मद (स.) सर्वांसाठी मोहिमेबद्दल काही विचारवंतांचे मनोगत.Dr Baburao Doddapaneni, Pain Management - YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0cLOn--iR8

May 14, 2014 - Uploaded by bharatmediatv

Dr. Baburao Doddapaneni, Pain Management, is the director of Greenwood Medical Services, a ...Jayapaul anna life story - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=LtjuGgqa2Y4

Jun 21, 2010 - Uploaded by samudrala phinehas

Jayapaul anna life story. ... Conference at paramankeni - Calvary Darshanam - Dr. N. Jaya paul ... Funeral ...Dr. Baburao Gurav Webcast_part 1 - YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFy9cUdh8N0

Jan 18, 2013 - Uploaded by Bharat4india

'सरकारच्या पैशांवर पोळ्या भाजून घेण्याऱ्यांचं नाही, तर कष्टकऱ्यांच्या भाजी-भाकरीवरचं हे संमेलन आहे', ...Dr. Babu Rao Chaparala, Birmingham, UK - YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HBkPF1Bdepk

May 20, 2014 - Uploaded by bharatmediatv

Dr. Babu Rao Chaparala, Birmingham, UK. bharatmediatv. SubscribeSubscribedV6 Zindagi - 'Cafe Nilofer' owner Buburao provides food to ...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fsfc6e5mICw

Oct 29, 2014 - Uploaded by V6 News Telugu

Babu Rao who worked in a hotel as cleaner now he owned the same hotel. He was born in Adilabad district ...Baburao dialogue by Prasad Bagul and sanmay deole ...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yqthst-tWJk

Aug 4, 2015 - Uploaded by Prasad Bagul

Raju: Prasad Bagul Baburao: Sanmay Deole. ... Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Song in Marathi - Desh ...The Patels of Filmindia - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vzsm3ozhqmY

Jun 15, 2015 - Uploaded by Indus Source Books

A must-read book on Filmindia—the iconic film magazine first published in the 1930s by the Patels—Baburao ...

Stay up to date on results for dr. baburao patel life story.

Create alertSearch Results

Baburao Patel - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baburao_Patel

Baburao Patel (1904–1982) was an Indian publisher and writer, associated with ... Girnar Publications; Burning words: A critical history of nine years of Nehru's ...Baburao Patel's Poisonous Pen | MemsaabStory

memsaabstory.com/category/hindi.../baburao-patels-poisonous-pen/

It features 36 actors and actresses, with a short biography of each accompanied by a gorgeous colored plate like the ones above. And though the book is ...FILMY INDIA: BABU RAO PATEL AND SUSHILA RANI PATEL

bmmann-filmyindia.blogspot.com/.../babu-rao-patel-and-sushila-rani-pat...

Apr 20, 2014 - Products - Dr. Baburao Patel's Homoeopathic Remedies ... SeeBaburao Patel Latest News, Photos, Biography, Videos and Wallpapers.Sushila Rani Patel: Film Industry Pioneer and Renaissance ...

pharaat.blogspot.com/2014/07/sushila-rani-patel-film-industry.html

Jul 28, 2014 - Sushila Rani Patel: Film Industry Pioneer and Renaissance Woman (1918 - 2014BABURAO PATEL | bio- Biography - Bollywoodnazar.com

www.bollywoodnazar.com/biography/celebrity/.../baburao-patel/bio/64

BABURAO PATEL- Biography,Filmography,Wallpapers, Videos, Movies, Photos ... most prominent was writer, actress, and journalist, Dr. Susheela Rani Patel.FilmIndia/Mother India MAGAZINE editor Baburao Patel

bombaymann2.blogspot.com/.../on-great-film-editor-baburao-patel.html

Baburao was born to an affluent family in the Konkan area of Maharashtra. ... wives, most prominent was writer, actress, and journalist, Dr. Susheela Rani Patel.Products - Dr. Baburao Patel's Homoeopathic Remedies

miponline.in/products.html

Results 1 - 20 of 129 - For all melancholias, mental distress; feeling of frustration; self-condemnation; thought of suicide; no love for life; profound despondency; ...The Patels of Pali Hill | The Indian Express

indianexpress.com › lifestyle › books › Eye 2015

Aug 9, 2015 - The Patels of Filmindia, Book Review, Baburao Patel, Film journals, Khushwant Singh ... by Indus Source Books, brings alive this forgotten slice of history. ... the late Dr Kotnis by adding 25 years to his age and several negroid ...What made me think of Him? | Sulekha Creative

creative.sulekha.com › General

Nov 7, 2010 - Baburao was born to an affluent family in the Konkan area of Maharash. ... was writer, actress, and journalist, Dr. Susheela Rani Patel. Baburao ...Dr. Baburao Patel vs Bal Thackeray And Anr. on 4 March ...

indiankanoon.org/doc/823786/

Dr. Baburao Patel vs Bal Thackeray And Anr. on 4 March, 1977 ... The Petitioner was offended by the contents of that article and therefore he filed a ... is the position of the complainant in life as a journalist on the basis of which according to the ...Write Your Life Story - Write, Share & Archive Life Stories

Adwww.therememberingsite.org/Relax, Reflect, Remember

Searches related to dr. baburao patel life story

Kharghar, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra - From your Internet address - Use precise location